afilasi

Black Experience Isn’t a spectacle

With the support of Anteism Books, afila.si shares its collective Afrofuturist digital library via special project presented at Printed Matter – Nada, Miami.

Black Experience isn’t a Spectacle encourages its audience to engage with Afrocentric knowledge productions, rather than through the voyeuristic gaze.

On this open platform, experience the collective’s premiere exhibition while directly engaging with its theoretical core. Aiming to build community, you can socially annotate and comment on the exhibition’s curatorial reflections and invite your friends to share their thoughts.

Each artwork presented is paired with a curated library, simply click the reference to be directly led to an open-source document for your study and enjoyment.

(Get Started)

Follow us on socials for future updates @afila.si

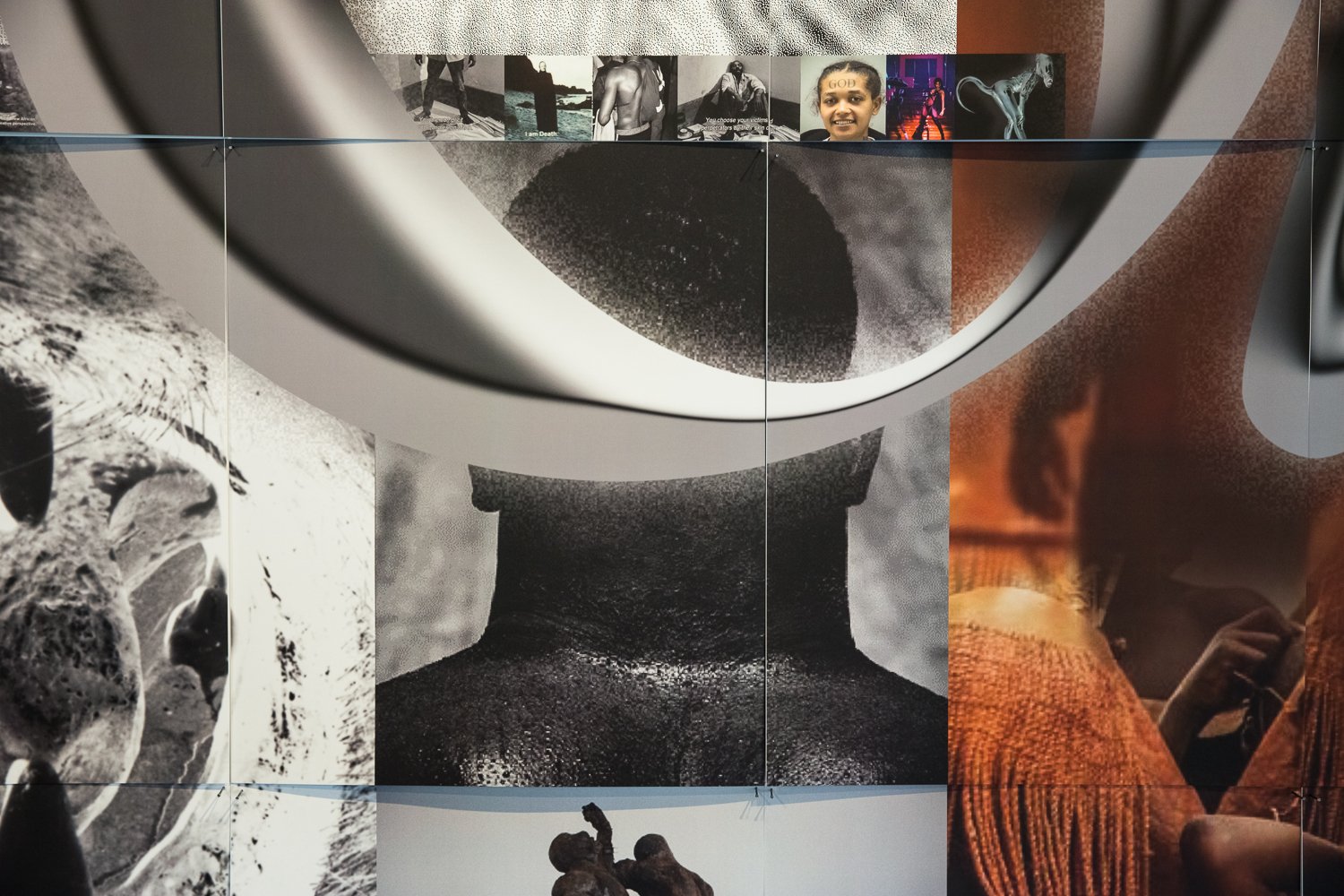

Close-Up of “Odd.er (Print)” artwork by Jesse Katabarwa. A modular referential print piece of 55 individual sheets.

Photography by Sabrina Jolicoeur.

For its premiere exhibition, afila.si presented Black Experience isn’t a Spectacle, which explores the legacy of the voyeuristic gaze in representations of the Black body. It intends to exist as a restorative gesture against the erasure of the Afrocentric perspective in [art] history. Combining the spatial elements of a visual art gallery and a reading room, afila.si and Anteism Books invited their visitors to engage with African descent individuals through the productions of our minds, our nuances and our non-monolithic approaches; rather than mere representation in the visual field. This is expressed through image sequencing, curated literary and cinematic circulation to be consumed through forms of embodiment with architectural sculptures. Black Experience isn’t a Spectacle offers a landscape of “counter-visualities”.

Learn how to share your thoughts and comments with other readers of this project.

There is power in looking. For the visibly ‘othered’, images play a pivotal role in defining and controlling access to political and social power. Visuality exists as a set of ‘psychic and discursive assemblages operating on the imagination and bodies of its subjects.’1 It operates as a source of subject formation and knowledge production.2 The deeply ideological nature of imagery determines not only how other people imagine us, but how we imagine ourselves.

Much is to be said on the visually-arresting nature of Black individuals. The historical roots of the camera’s lens onto the African continent inform the standing traditions of visualizing the Black body. During the colonial Scramble for Africa, a new artform, film was in its early stages. Known as ‘The Cinema of Attractions’ (1895-1907), this film style emerged with a focus on the act of showing and exhibition. Stripping the craft to its core, this period is representative of the unique power of the photographic image; it’s ‘harnessing of visibility.’3

Danse du Sabre, II. Lumière: View N° 442. [May 23rd 1897.] The Lumières Brothers’ African Corpus.

These images were taken in an exhibitionist mock-village of Ashantis peoples set in Lyon, France. Two performers mime a fight to the sound of tam-tam drums and the clapping of hands for the enjoyment of European crowds.

The first time Sub-Saharan Africans were subjected to the cinematic lens was in the context of fulfilling the Western voyeuristic gaze. In 1896, the Lumières Brothers began shooting a series of 14 films showcasing a group of Ashanti people from the Gold Coast [today’s Ghana].4 They had been imported to perform in French human zoos. The interest of the Cinema of Attractions was to ‘incite visual curiosity [and] supply pleasure through an exciting spectacle.’5 What nurtured idealized senses of white superiority was the expository visualization of blatant differences. Within itself, the photographic apparatus was used as an enabling tool for the process of othering the Black body. The right to look, this ‘harnessing of visibility’ is an intersubjective process that implies a distance. For Sub-Saharan Africans, and their descendants, the history of visuality was a colonial project of intrusion. As Stuart Hall states; ‘They had the power to make us see and experience ourselves as Other.’6 Indeed, visuality operates aesthetically to legitimize primarily Eurocentric visions of geopolitics.7

Close-Up of “Odd.er (Print)” artwork by Jesse Katabarwa. A modular referential print piece of 55 individual sheets.

Photography by Sabrina Jolicoeur.

It’s important to anchor the fact that the visual field is not neutral to the question of race; it is itself racial formation. The visual sphere is a performative one where seeing race is an active act.8 Thus, visuality is a crucial field when we consider its place in Black livelihood and the connections between the social construction of Black identity. When we consider ‘the presence of black life in an inarticulate, but ever-present visual aesthetic governing our relationship to the process of image-making.’9

Mere visual representation isn’t the answer. Its link with domination maintains it as a place of struggle. There’s a concern on our heavy simplistic reliance on visual narratives with realist aesthetics to get at the heart of the Black experience. The false expectation that representation itself – Black iconicity, will resolve the problem of the Black body in the field of vision only encourages normative discourse. Accordingly, Blackness becomes visually knowable through its performance. ‘So Black life becomes intelligible and valued, yet also consumable and disposable.’10 In this sense, Blackness circulates – but it isn’t rooted in a history…

Black Experience isn’t a Spectacle attests to how these historical dynamics amalgamate to the normalized erasure in today’s realities. Black livability goes beyond its reductions to exhibitionism, scrutiny, fetishization and an entertaining provision for the intruder’s gaze. Whether in film, music, sports, or even until the visualization of its slaughter, Black bodies are put on constant display and subjected to voyeurism. Our title centers on the concept of spectatorship as we aim to redefine how we look, spectate and culturally consume Blackness. ‘Let’s question the production, reception, accessibility and circulation of Black visuality.’11 The featured artists intend to reclaim this gaze using that power within the ‘matter of making images seen’ as means to create narratives embedded in contemporary experiences of the [African] Othered. Combining the spatial elements of a visual art gallery and a reading room, Black Experience isn’t a Spectacle offers a landscape of ‘counter-visualities’.12 .

Beyond iconographic representation, our audience engages with Afrocentricity through the productions of thought with a curated library. Each collection of this library interacts with image-sequencing through print and audio-visual , as well as, through physical embodiment with Bantu architectural sculptures. These add to the universal library of Black cultural productions with a subaltern experience and re-assertion of the ‘right to look’. The artworks allow for a reformulation to transform a detrimental quality of blackness – the spectacle – into an emancipatory virtue.

Curatorial Statement by Venessa Appiah

Close-Up of “Odd.er (Print)” artwork by Jesse Katabarwa. Canine image courtesy of Justina Vilutis. A modular print piece of 55 individual sheets.

Photography by Sabrina Jolicoeur.

Blissfully, we surrender to the whirling blackness of consciousness

Blissfully, we surrender to the whirling Blackness of our bodies and spirit

within the darkness of the earth, is where blissful life comes from13

Odd.er (Audio-Visual)

Jesse Katabarwa :

Concept and Creative Direction

Ouri and Tati au Miel :

Sound design

Christian Boakye :

Video Editing and 3D animation

Venessa Appiah, Sona Sadio and Daouda Ka :

Content Researcher

Odd.er (audio-visual) is rooted in the purity of emotion that is embodied through image sequencing. A process of exercising the muscle of empathy within fellowship through expressions of vulnerability. This piece centers the remixing of images and the concepts of circulation and accessibility.This this It democratizes what is original within a concise space.

The audio scoring of this composite by Tati au Miel and Ouri is intended to follow the cadence of the imagery. As well as, representing the growing pain and a mounting inner intensity .There is an interest in the almost schizophrenic and ADD contemporary consumption of images and sound. Jesse Katabarwa, Rwandan emergent artist mixes and remixes visual works and curates a selection of references to create new narratives. Which is reminiscent of the manners in which early DJs would appropriate music to embody a new experience.

Ibiyanε

ibiyanε is the name of the ongoing conversation around furniture designed and hand-crafted by Elodie Dérond and Tania Doumbe Fines.

Their debut collection, self-titled ibiyanε is a body of sculptural chairs embedded in Sub-Saharan African reflections of physicality. Within the space, paired with a curated library, this collection extensively stimulates engagement with self and independence in thought. Through Bantu design languages, they create dialogue with modern Western conception of furniture design; a reflection of a deeply rooted hyphenated identity.

Dérond and Fines’ practice within traditional methods of craftsmanship and all that it entails; patience, mindfulness and total engagement of the body and spirit. Working in symbiosis, their dexterity truly embodies what ibiyanε reveals in native Batanga; to know one another. Utilizing wood as its sole material, these chairs come to being with the least industrial methods of assembly.

Artwork Genesis by Tania Doumbe Fines and Elodie Dérond courtesy of Ibiyanε. Photography by Karl Obakeng Ndebele.

African Birthing Chair, Genesis

Genesis : A birthing chair, also known as a birth chair, is a device that is shaped to assist a woman in the physiological upright posture during childbirth. It is intended to provide balance and support. The birthing chair can be traced to Egypt in the year 1450 B.C.E. Pictured on the walls of The Birth House at Luxor, Egypt, is an Egyptian queen giving birth on a stool. Birthing chairs fell out of use after physicians began using the flat bed for women to lie on during delivery. The concept of the birthing chair has also been written in observations by anthropologists as well as missionaries. Most are associated with Western Africa and countries such as Nigeria. The religious and medical practices are pretty much entwined in the culture, the squatting position has religious overtones, as the contact with the earth indicates fertility. These chairs are usually no more than 8-10 inches off the ground so that the woman could brace her feet on the ground to assist with pushing. This chair is considered as a family heirloom and passed down through the family line.

Material : Tainted birch plywood

Carving : The design is a transcription of a traditional Cameroonian geometric pattern found in African Design: From Traditional Sources by Geoffrey. Williams

Literary References Related to Genesis

Maya Angelou

Africa

Michael Onyebuchi Eze

Pan-Africanism and the Politics of History

Aimé Césaire

Return to my Native Land

Osuanyi Quaicoo Essel & Ebenezer Acquah

Conceptual Art : The Untold Story of African Art

Cheikh Anta Diop

& Mercer Cook

The African Origin

of Civilization :

Myth or Reality

Cheikh Anta Diop

& Harold Salemson

Precolonial Black Africa

Cheikh Anta Diop

Civilization or Barbarism

Erik Gilbert &

Jonathan T. Reynolds

Africa in World History :

from Prehistory to

the Present

Alain Locke

The New Negro

Vincent B. Khapoya

The African Experience :

an Introduction

Colin Legum

Pan-Africanism;

a Short Political Guide

V. Y. Mudimbe

The Invention of Africa :

Gnosis, Philosophy and

the Order of Knowledge

Artwork Elombe 002 by Tania Doumbe Fines and Elodie Dérond courtesy of Ibiyanε. Photography by Karl Obakeng Ndebele.

Elombe 002

The conceptualization stems from a similar joinery as the African Birthing Chair. A plank inserted into another, in order to create support. The seating and dossier lock in a harmonious way. The two parts complete and live within each other, like a sun kissing the horizon of an ocean. Working in symbiosis, their dexterity truly embodies what Ibiyanε reveals in native Batanga; to know one another.

Literary References Related to Elombe 002

Artwork Elombe 007 by Tania Doumbe Fines and Elodie Dérond courtesy of Ibiyanε. Photography by Karl Obakeng Ndebele.

Elombe 007

The conceptualization reflects a throne with a minimalist influence. A symbol of power, heritage and strength, seen from an Afro-futuristic lens. It's dark finish is reminiscent of a dystopian past, while its sleek and refined elongated proportions project us in a future filled with knowledge. Through Bantu design languages, they create dialogue with modern Western conception of furniture design; a reflection of a deeply rooted hyphenated identity.

Literary References Related to Elombe 007

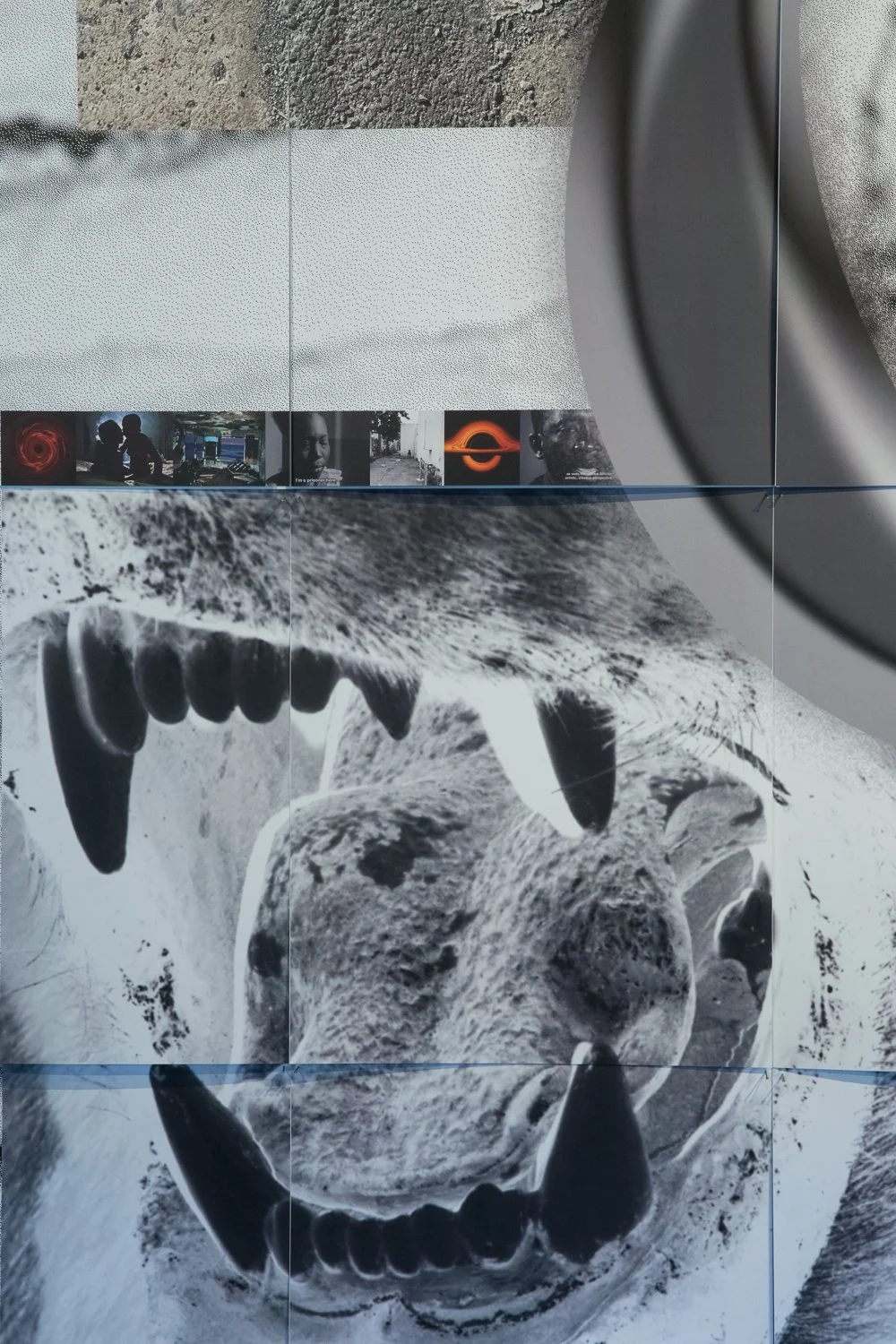

Artwork Black Stigmas from Diptych Body Qualm by Jesse Katabarwa. Image courtesy of the artist.

Body Qualm

Diptych – by Jesse Katabarwa

Body Qualm is a pictorial research which reveals in one instance, whiteness visually rendered as unscathed godly purity. As a social construct and a powerful fiction, it centers itself as the ideal. Ostracizing all that is outside the mold of its representation. From this perspective, unravels the social construct of Blackness and its contrasting imposed stigmas. As a contraposition, this portrayal embodies preconceptions put upon the Black being coined during the colonial era bleeding into mainstream culture today. Seen as the hyper-physical, hypersexualized body; innately violent, savage, disorderly.

This diptych is a materialisation of juxtaposed non-sequential references, resulting in a highly subjective and ambiguous appeal. It offers an alternative representation to the postmodern “fragmented and schizophrenic decentering and dispersion” of the body. Body Qualm confronts the viewer's own physicality with these pseudo-scientific narratives. Visually depicting these fabricated ideals make them tangible, palpable; and their effects on our realities, undeniable.

Literary References Related to Body Qualm

Artwork Diasphora by Jesse Katabarwa. Image courtesy of the artist.

Diasphora

Triptych by Jesse Katabarwa

Diasphora is a research project exploring the ways in which Black and East Asian identities are framed within mainstream narratives. This triptych represents the essential gap between these narratives but also their points of symbiosis within historical realities and personal experiences. Emphasizing the hegemonic, yet oversimplified gaze upon Othered bodies. The viewer’s own gaze becomes the spectacle of this piece as it is physically reflected upon themself through glass.

diasphora

noun [dhy-as-fawr-uh] diaspora + dysphoria

The unease or feeling of having no sense of home. Eternally displaced , forever the other, without sense of self; a blurred identity. A dismantling of the body.

Literary References Related to Diasphora

1 Mirzoeff, Nicholas. The Right to Look : a Counterhistory of Visuality . Duke University Press, 2011. Back to text

2 Fleetwood, Nicole R. Troubling Vision Performance, Visuality, and Blackness . University of Chicago Press, 2011. Back to text

3 Strauven, Wanda. The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded . Amsterdam University Press, 2006. Back to text

4 “Lumieres Brothers & Africa” Lecture by Dr.Aboubakar Sanogo Back to text

5 Strauven, Wanda. The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded . Amsterdam University Press, 2006. Back to text

6 As quoted in : hooks, bell. Black Looks : Race and Representation . South End Press, 1992. Back to text

7 Mirzeoff, Nicholas. The Right to Look : a Counterhistory of Visuality . Duke University Press, 2011. Back to text

8 Fleetwood, Nicole R. Troubling Vision Performance, Visuality, and Blackness . University of Chicago Press, 2011. Back to text

9 hooks, bell. Black Looks : Race and Representation . South End Press, 1992. Back to text

10 Fleetwood, Nicole R. Troubling Vision Performance, Visuality, and Blackness . University of Chicago Press, 2011. Back to text

11 hooks, bell. Black Looks : Race and Representation . South End Press, 1992. Back to text

12 Term coined by Nicolas Mirzeoff Back to text

13 Inspired by Sylvia Plath’s poetry. Back to text